The Genre Trail – You Have Died of Disinterest

This isn’t a normal blog post. As you might know my name is Jukka Kovalainen and I’m the Process Leader and Technical Engineer here at Embracer Games Archive. Basically the tech guy. My background is in computer science and IT architecture, with database design as my main focus.

The reason for this article is that quite often I get a question regarding Metadata in the archive and what we need and what we want. Genres come up quite often as a question about whether it’s something we record. But, as of this moment, it’s not. That will most likely change in the future as the database grows, but time will tell.

This does, however, raise the question as to why we don’t have genres, but it pointed me in another direction. What kind of data would we have, and how would it be useful?

There is a TL;DR at the end if you want to skip my ramblings.

Road Trip Simulator: Genre as Destination

I either read it or just made it up.

Somewhere, “Road Trip Simulator” was used as a genre label and it stuck with me half-remembered in my subconsciousness. A genre that felt true, somehow.

One with a beginning, a journey, an end. Obstacles to overcome. Resources to manage. A sense of purpose through motion.

I started thinking: Why hasn’t this been seriously discussed?

Not just the idea of a road trip as a theme—but as a structural genre, something that shapes how a game feels and plays.

If you try to flatten this into a static genre map, then you have lost the trail.

What genre is The Sims? A simulation? A strategy game? A sandbox? A psychological horror in suburbia when someone higher power removes the pool ladder?

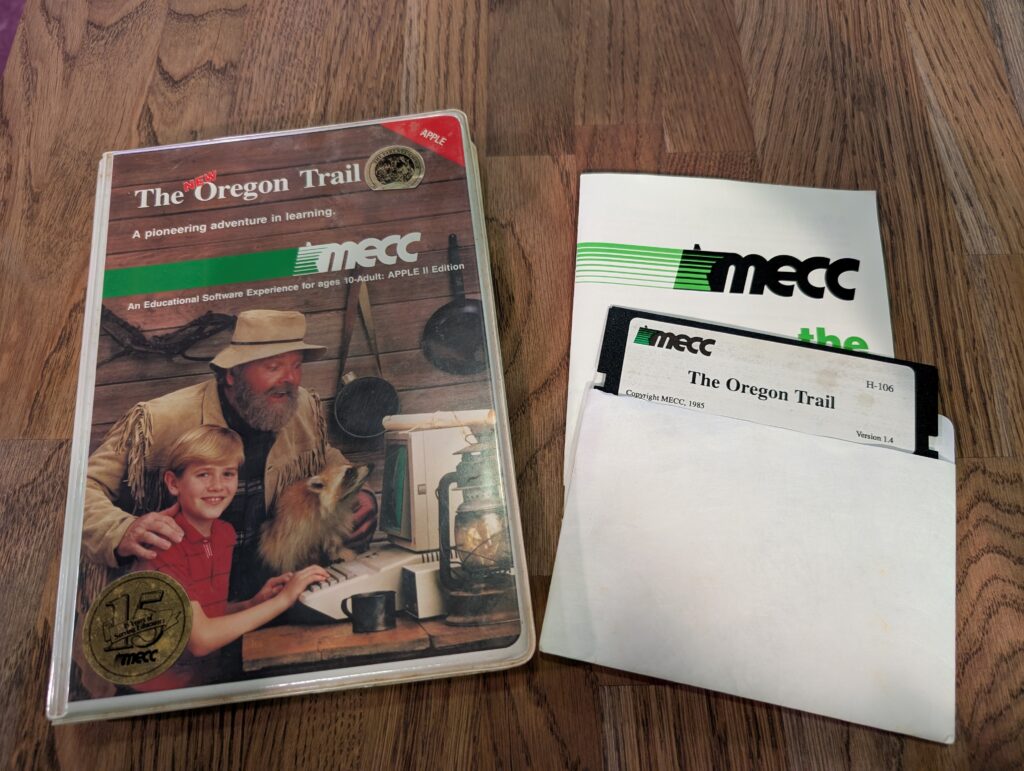

What about Oregon Trail? A historical educational game? A survival RPG? A proto-road trip simulator?

The more time you spend with video game genres, the more they start to feel like trying to herd cats. Or maybe wild buffalo is more apt in this setting.

Every attempt at definition either collapses into marketing language (Action! Adventure!) or becomes so specific it’s unusable (Semi-linear Environmental Puzzler With Roguelike Loop and NPC Capture Mechanics).

We need genres. But they are broken. And the more we try to fix them, the more we risk losing what they meant in the first place.

Genres Are Ghosts of Culture and Marketing

Genres aren’t technical specs. They’re cultural phenomena. They emerge from player communities, marketing trends, historical context, and a mess of shared assumptions.

They drift. They decay. What we called a “CRPG” in 1985 was about numbers and dungeon crawling. What we call an RPG now includes visual novels, farming sims, dating games, and whatever Genshin Impact is.

I once had a conversation at a conference with Vojtěch Straka of Herní historie. He mentioned that genres may still have archetypal traits. And he’s right, to a point. But archetypes get corrupted. They degrade over time, reinterpreted by players and publishers alike.

Take Adventure on the Atari 2600: it’s an archetypal “adventure game”. But also an action game, proto-immersive sim and maybe a horror game, if being chased by a dragon that looks like a duck scares you.

Genre Isn’t a Field – It’s a Hypercube

I’ve had similar discussions lately with Jan Kremer of Národní filmový archiv, Willem Hillhorst of The Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision, Winfried Bergmeyer of Internationale Computerspielesammlung and multiple others from the EFGAMP group and I mentioned that I needed to write this article. Where we have discussed the problem itself and I’m deeply grateful to all of you. And of course, I must mention our Natalia Kovalainen from Embracer Games Archive as I’ve been pestering her with my ideas for quite some time.

The problem begins when we try to make genres act like database fields. We want clean rows. Searchable columns.

But genre is not a dropdown menu. It’s a hypercube as I both jokingly call it and use as a placeholder name.

Each game exists across multiple axes:

• Narrative Domain (Story–Aesthetic)

Is it a Road Trip? A Ritual? A Loop? A Collapse? What does it evoke? Cyberpunk? Cozy game? Horror?

• Mechanical Domain (Play–Interaction)

Is it turn-based? First-person? Rhythm input? Is it top-down? Side-scrolling? Embodied?

• Social Domain (Human–Contextual)

Is it about mastery? Dread? Discovery? Do you play it alone or with friends? How was it marketed?

• Temporal Domain (Historical–Evolving)

Is Metroid a Metroidvania style game? When did that term even appear? How do genres shift as time, technology, and culture reinterpret them?

Games like Inscryption, Immortality, Undertale or Death Stranding that don’t fit into single genres. They’re multi-dimensional experiences. Reducing them to one tag is like calling Blade Runner “a cop film.”

My proposal:

- Narrative Domain (Story–Aesthetic)

Describes how the game feels, unfolds, and expresses meaning.

It captures story structure, emotional resonance, and aesthetic signature.

| Axis | What it Describes | Example Values |

| Primary Archetype | Narrative / Emotional structure | Road Trip, Descent, Ritual, Awakening, Horror, Enlightenment |

| Aesthetic Genre | What it looks like or evokes | Cyberpunk, Pastoral, Minimalist Horror, Y2K Trashcore (refer to Metadata Tags) |

| Pacing | How time behaves narratively | Real-time, Turn-based, Time-looped, Pressure-timer |

- Mechanical Domain (Play–Interaction)

Describes how the player acts and how the system responds.

It defines the interactive grammar and material interface of play.

| Axis | What it Describes | Example Values |

| Core Loop | What you do repeatedly | Kill → Loot → Upgrade, Talk → Explore → Reveal, Farm → Craft → Trade |

| Mechanical Interface | How you interact | Keyboard, Mouse, Light Gun, Rhythm Input |

| Perspective | Camera and embodiment | Isometric, Sidescroller, Top-down, Embodied POV |

| Simulation Density | How deep systems go | Abstracted, Layered, Hyperreal |

- Social Domain (Human–Contextual)

Describes who you play with, what motivates you, and how it exists culturally.

It includes both player configuration and market framing.

| Axis | What it Describes | Example Values |

| Social Dynamics | Who you’re playing with or against | Solo, PvP, PvE, Co-op, Asymmetric |

| Legacy Marketing Genre | For compatibility with pre-existing classifications | Action, RPG, Puzzle, Simulation |

| Metadata Tags | Freeform modifiers and memetic genres | Roguelike, Cozy, Metroidvania, Boomer Shooter |

- Temporal Domain (Historical–Evolving)

Describes how genres evolve, re-emerge, and transform over time.

It situates the game within its historical, technological, and linguistic context recognizing that genres are processes, not fixed containers.

| Axis | What it Describes | Example Values |

| Cultural Phase | When the defining term or style emerged | 8-bit Era, Early Indie, Post-AAA, Revivalist |

| Genre Drift | How interpretation or usage changed | “Adventure” (1980s text) → “Action-Adventure” (2000s) |

| Technological Layer | Platform and affordance shifts | Arcade → Console → PC → Cloud |

| Semantic Lineage | How terms reference older works or memes | Metroid → Metroidvania, Doom → Boomer Shooter |

Who is this for?

Well right now it’s for no one. This is a proposal and very overworked one at that. Truthfully it is very unlikely to be used in full. Still, some fragments might prove useful to someone developing a database. We have no grass for oxen.

The Trouble with Taxonomy

Before we can build typologies or ontologies, we need a common language.

And right now, we don’t have one. No water for oxen.

We can’t even agree on what to call a game.

In Swedish, spel means both game, theater, gambling, and more. TV-spel made sense when games were plugged into televisions, but what happens when they’re played on a monitor, or a phone, or a headset? And what about a new game developed by Noah Molteberg Lundén called Blind Survival right here in Värmland? You play as a blind person guided only by sound. Is that still a TV-spel or Video Game?

If our words can’t keep up, our databases never will.

Search DigitaltMuseum.se for train and you’ll find around 300 results.

Search tåg and you’ll get nearly 19 000.

Station returns about 35 000. Why so many results?

Station is used by Swedish, Danish, English, Dutch and multiple other languages.

Different words for the same thing but the system doesn’t know that.

There’s no parallel entry that says:

1. Category(en): Game

2. Kategori(de): Spiel

3. Kategori(se): Spel

We have no cross-reference, no shared taxonomy for even the simplest concept.

Do we have a textbook definition? If all of these are “digital games,” then what about the Magnavox Odyssey: analog signals, digital-transistor logic and plastic screen overlays?

Every attempt at building an ontology ends up revealing its own cultural bias. DigitaltMuseum, IGDB, MobyGames; they all decide, silently, what counts as a game and what doesn’t. These decisions aren’t neutral. They define the borders of play itself.

So, when we talk about building an ontology for games; something that could link archives, databases, museums, and collections We’re trying to build on unstable foundations. An ontology connects ideas, but it can’t decide what those ideas are.

That’s taxonomy’s job. And taxonomy, right now, is broken.

What is a “Digital game”?

Electronic? Computer based?

Is a coin toss, heads or tails, digital?

Does Magnavox Odyssey count?

Does a Game & Watch?

At what point does electronic become digital, or toy become game?

Until we can name these boundaries, we can’t describe or relate them.

In short: we have no water, no grass for the oxen and we’ve lost the trail.

We know where we are going but not how to get there.

Taxonomy is where it starts.

It’s the foundation that lets typology describe structure, and ontology connects versions and archives.

Without it, every database, every collection, every research project becomes its own small island each with its own word and definition of a game.

And while I’ve been wasting yours and my time reading this proposal of a new Genre system, I hope to have at least piqued your interest in why we need a taxonomy before we can define typologies. My proposal is also peppered with points where taxonomy shows itself. Terms like Loot, Shoot. Mechanics like Isometric, keyboard and so on.

But unless we call a mouse for a mouse and not a pointing device, we can hardly define what a Road Trip is. Now get in the wagon, pioneer! Let’s hit the trail!

TL;DR

Genres aren’t fixed categories. They’re shifting, messy cultural constructs, which is why traditional labels fail. My proposed multidomain framework (narrative, mechanical, social, temporal) is just a draft, meant as a guide to show how complex genres really are and to inspire others to design what their own databases need.

Different institutions track different things like memories, objects, mechanics, stories. No single system will fit all. What matters is building a shared taxonomy, a common language, so our databases can understand each other. Without that common foundation, every archive becomes an isolated island.